A Photographer's Guide to the Ecology and Wildlife of Serengeti National Park

Few places on Earth capture the majesty of Africa like Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. Stretching across northern Tanzania, this vast savanna is home to the largest land migration on the planet and some of the most iconic wildlife encounters anywhere.

For centuries, Maasai pastoralists grazed their cattle across these plains, calling it Siringet - “the place where the land runs on forever” or the “endless plains.” Today, the Serengeti is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s most important ecosystems for wildlife conservation, research, and photography.

As a wildlife and conservation photographer living in Tanzania, it’s no surprise that the Serengeti is my favorite place to work. One thing it teaches you quickly is that understanding your subjects makes a huge difference in your photography. The more you learn about how this ecosystem functions, the easier it becomes to predict behavior and craft photos with purpose.

In this guide, I want to share some of the ecological and natural history patterns that shape its landscape, and how knowing a bit of that background can help you experience and photograph the Serengeti in a deeper, more rewarding way.

A Living History of Serengeti National Park

The Serengeti’s story is woven through layers of geologic upheaval, shifting climate, and human presence. The East African Rift carved the region’s plains, kopjes, and valleys, while volcanic ash from the nearby Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano enriched the soils that now support the Great Migration. Over hundreds of thousands of years, cycles of wet and dry sculpted the mosaic of grassland, woodland, and riverine forests that we see today. Fossils show that many familiar species like wildebeest, zebras, and lions have roamed the Serengeti for over a million years.

Human history here is just as deep. Not far from the park is Olduvai Gorge, where Louis and Mary Leakey uncovered early human ancestors like Homo habilis and Australopithecus boisei, showing that this landscape helped shape our own story too. For centuries, the Maasai and other communities such as the Ikoma, Kurya, and Sukuma lived around the ecosystem, following seasonal rains and sharing space with resident wildlife.

The modern conservation era began in the early 1900s when colonial administrators and trophy hunters documented the region’s remarkable wildlife abundance. A partial game reserve was established in 1929, leading to the creation of Serengeti National Park in 1951. Later, Bernhard Grzimek’s film Serengeti Shall Not Die brought global attention to the importance of protecting this space. Since Tanzania’s independence, the Serengeti has become a cornerstone of the country’s conservation identity and one of the best-preserved landscapes on Earth.

The Serengeti’s Ecology and Wildlife

Covering more than 14,000 square kilometers, Serengeti National Park is far more varied than people expect. There indeed are endless plains, as well as acacia woodlands, rocky kopjes, seasonal swamps, and river corridors. In the Serengeti, rainfall is the engine behind almost everything. The nutrient-rich short-grass plains in the south grow quickly after the rains, while the wetter central and northern regions stay green longer, creating pockets of abundance even in the dry season. These variations shape where animals are found, as well as how they behave, from daily foraging patterns to seasonal movements.

Ungulates and other herbivores form the foundation of the ecosystem. Beyond the famous migrating herds are vast populations of gazelles, topis, hartebeests, buffalo, waterbuck, giraffes, eland, and warthogs. Each occupies a distinct ecological niche, minimizing competition and shaping the land through grazing, trampling, and seed dispersal. Their behavior is finely tuned to survival. Thompson’s and Grant’s Gazelles move in tightly coordinated groups to detect predators, and elephants travel in matriarch-led family units that remember water sources and safe routes. Even seemingly random movements by smaller herbivores can influence predator behavior and plant regeneration across the plains.

Predators are equally abundant and exhibit fascinating social dynamics and hunting behaviors. The Serengeti supports an estimated 3,000-4,000 lions, around 1,000 leopards, and roughly 500-600 cheetahs, alongside some 7,500 spotted hyenas. Lion prides coordinate hunts, defend territories, and care for cubs in ways that ensure long-term survival, while leopards use stealth and tree cover to avoid competition with larger cats. Cheetah mothers teach their cubs patience, stalking, and sprint timing, and hyenas demonstrate remarkable intelligence, using complex social hierarchies and vocal communication to coordinate clan activity. Even the smaller carnivores like caracal, serval, and African wild cats exhibit nuanced strategies for hunting and avoiding larger predators.

Above it all, more than 500 bird species animate the skies and woodlands, from vultures and tawny eagles to Fischer’s lovebirds, kori bustards, lilac-breasted rollers, and Tanzania’s largest concentration of wild ostriches. Birds influence the ecosystem by dispersing seeds, managing pests, and warning other animals of danger. Many species show remarkable intelligence and social learning.

Taken together, these behaviors reveal the Serengeti as a dynamic, interwoven ecosystem. Daily routines, predator-prey interactions, and seasonal migrations are all expressions of survival strategies honed over millennia. For wildlife photographers, noticing these patterns can help us anticipate behavior and make images that feel alive with context.

Witnessing the Great Migration

Every year, more than 1.3 million wildebeest, 200,000 zebras, and hundreds of thousands of gazelles traverse the Serengeti–Mara ecosystem in one of the most extraordinary natural events on Earth. This vast, circular journey spans roughly 1,000 kilometers and is driven by the search for fresh grazing and water in an ever-changing environment. What appears to be a single, sweeping movement is actually a highly dynamic system shaped by the interplay of rainfall, vegetation growth, and herd behavior in a journey refined over millennia.

Rainfall acts as the invisible conductor of the Serengeti’s Great Migration. Seasonal rains stimulate the growth of fresh, nutrient-rich grasses. As the wet and dry patterns rotate across the ecosystem, the herds follow this patchwork of temporary abundance. Wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles respond to the immediate presence of new growth, as well as subtle environmental cues such as humidity, scent, and the texture of the soil. These signals that tell them where water and food are most abundant. This coordinated movement spreads grazing pressure across the landscape and allows plants to recover and maintain the productivity of the plains.

Herd behavior is a fascinating part of the story. Individuals move in large, cohesive groups, balancing the risk of predation with the need to find food. Collective decision-making, sometimes described as “swarm intelligence,” ensures that small directional choices by individuals ripple through thousands of animals, guiding the group along traditional routes. Older animals may carry geographic memory and pass down knowledge of river crossings, calving grounds, and seasonal refuges. Constant movement also has a hidden benefit by rotating grazing areas, allowing the herds to reduce parasite loads and minimize disease, keeping populations healthier across generations.

From December to March, calving occurs on the southern plains around Ndutu, where every year an estimated 400,000 baby wildebeest are born within the span of just a few weeks. As the rains fade in April and May, the herds move north through the central and western Serengeti, eventually crossing the Grumeti River. Between July and October, the migration reaches its most dramatic stage at the Mara River, where crocodiles lie in ambush and strong currents test the animals’ endurance. With the return of November rains, the herds begin the long journey back south, completing the cycle once again.

Exploring the Regions of the Serengeti

The Serengeti is far from uniform. Its vast expanse encompasses a series of ecological zones, each with distinct landscapes, wildlife behaviors, and seasonal patterns that together sustain the park’s extraordinary biodiversity.

The Central Serengeti, around Seronera, forms the ecological heart of the park. Permanent rivers and scattered woodlands create reliable water and food, supporting year-round concentrations of wildlife. Predators such as lions, leopards, and cheetahs establish territories here, while herbivores exploit the predictable grazing. The central plains are a living laboratory for observing interactions between predators and prey, from hunting and avoidance strategies to herd dynamics.

In the Southern Serengeti, particularly Ndutu, the short-grass plains burst to life during the calving season. Mineral-rich grasses provide for lactating mothers and newborn wildebeest, drawing a surge of predators that take advantage of this short-lived windfall. Here, you can witness the delicate balance between reproduction, predator pressure, and survival strategies. Remarkably, the synchronized calving phenomenon is itself an adaptive behavior that dilutes risk for individual calves.

The Western Corridor, including the Grumeti region, is a mosaic of riverine forests, rolling hills, and acacia woodlands. Seasonal migrations funnel animals to the Grumeti River, where giant Nile crocodiles await. The corridor also supports resident species such as topi, elephants, and colobus monkeys. Observing how herds navigate this patchwork of habitats provides insight into habitat selection, predator avoidance, and the trade-offs animals make between food, safety, and energy expenditure.

The Northern Serengeti, encompassing Kogatende and Lamai, is remote, wild, and dominated by the Mara River and its dramatic seasonal crossings from July through October. Here, the interaction between the Mara River and herd behavior becomes most apparent. Wildebeest and zebra judge currents, crocodiles, and predator positions, making split-second decisions that are critical for survival. The northern plains also serve as refuge for resident species outside migration periods, including elephants, giraffes, and lion prides, highlighting how differences in landscape shapes animal distribution.

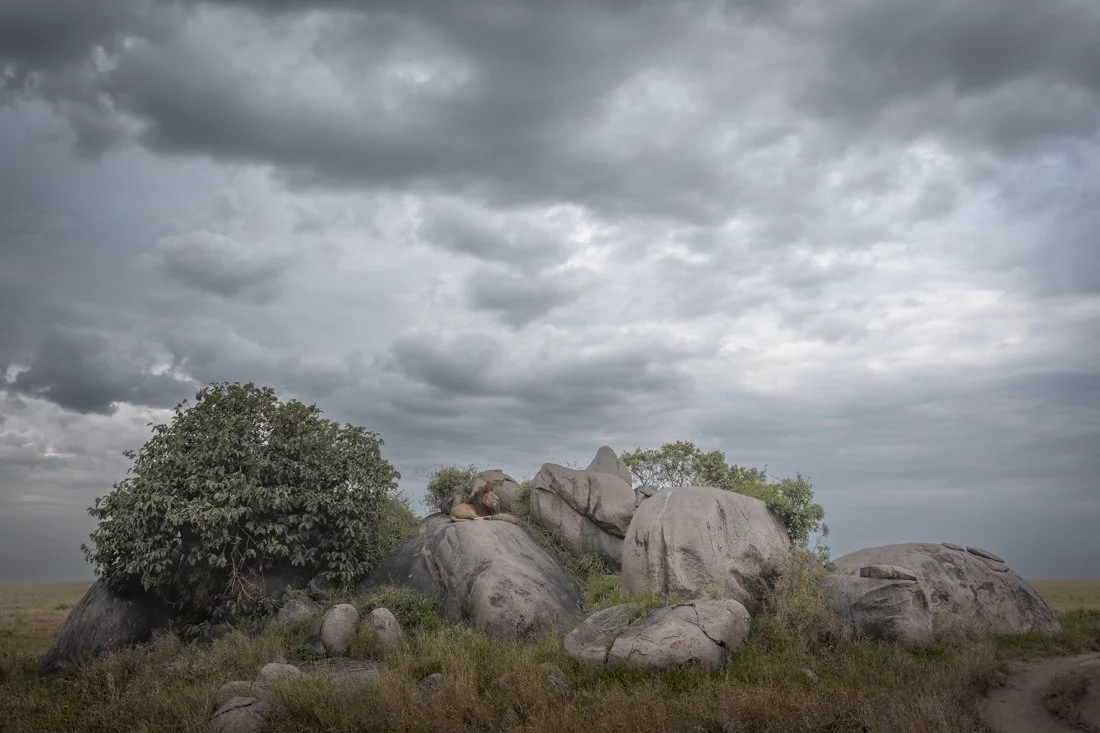

Finally, the Eastern Serengeti, including Namiri Plains, offers expansive grasslands punctuated by granite kopjes. These open plains favor the stealth and speed of predators such as lions and cheetahs, whose hunting strategies are influenced by the sparse cover and visibility. The region truly shows how terrain and vegetation shape predator-prey interactions, territory use, and even social behaviors of its resident wildlife.

Together, these regions illustrate the Serengeti’s ecological diversity and provide wildlife photographers with a rich variety of behaviors and environments to explore creatively. From river corridors to kopjes, each landscape influences how animals move and behave, creating the rich tapestry of life that has made the Serengeti one of the most studied and celebrated ecosystems on the planet.

Conservation and Protecting the Serengeti’s Delicate Balance

The Serengeti’s resilience comes from a balance of ecological forces - predators and prey, fire and rain, migration and recovery. Keystone species like lions, elephants, hyenas, and wildebeest keep the ecosystem functioning at continental scale.

Maintaining connectivity across the greater ecosystem is also essential. Migration corridors allow animals to follow rains and maintain genetic diversity. As climate change shifts rainfall patterns, keeping these pathways open will become even more important.

Human communities are part of this balance too. Efforts like predator-proof livestock enclosures, wildlife corridors, and community-based tourism help reduce conflict and support local livelihoods. Tourism revenue also funds anti-poaching operations, habitat restoration, and scientific research. Together, this helps to maintain the very processes that make the Serengeti one of the most remarkable and enduring ecosystems on Earth.

Despite its scale and protections, the Serengeti faces growing pressures. Expanding communities around the park experience crop losses from elephants and livestock predation from lions and hyenas. Wildlife corridors are narrowing due to agriculture and settlement, threatening the migration’s ancient pathways. Inside the park, bushmeat poaching, climate-driven changes in rainfall, and increasing tourism add further complexity.

Yet the Serengeti remains remarkably resilient. Community-led conservation and initiatives that address the needs of both human and animal populations are key to safeguarding the future of this incredible ecosystem. The challenge ahead is to ensure that human needs and landscape protection remain in balance, a task requiring collaboration across communities, government, and the rapidly expanding tourism industry.

Understanding the ecology and fragility behind these processes makes every visit richer. It helps you appreciate why animals gather where they do, how seasonal changes shape behavior, and why such a special place deserves our respect and protection.

A Landscape That Defines the African Wilderness

The Serengeti is one of the last places on Earth where ecological processes still unfold on a truly grand scale. It is a living system shaped by storms, grass, predators, migration, and time itself.

To stand on its plains is to witness a world that has changed surprisingly little over millennia, where wildlife still moves freely and where the connection between land and life remains beautifully visible. Whether you come for the big cats, the migration, or the immense sense of space, the Serengeti has a way of staying with you long after you’ve left.

Ready to turn inspiration into experience? Join me in April 2026 for my Big Cats of the Serengeti photo safari, a bespoke, expert-led adventure designed to elevate your wildlife photography in one of the most extraordinary places on Earth.